The Assignment That Talks Back: Replacing One-Time Papers with Conversations That Adapt to Each Student

What happens when you replace a static letter with a dynamic bot? An experiment in AI-assisted self-discovery at scale

Bottom Line Up Front

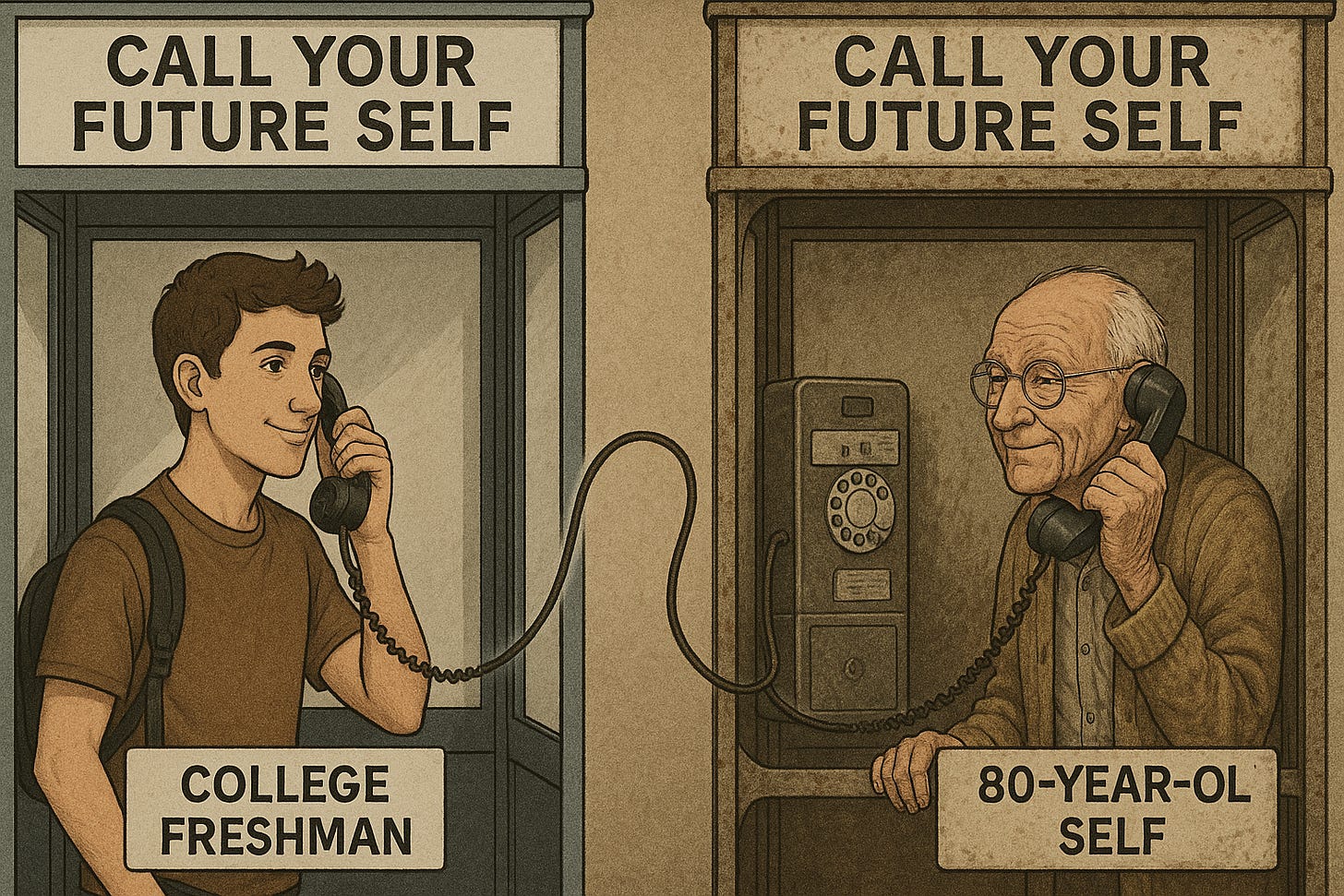

When you have 750 incoming freshmen who need personalized guidance about their future but only limited faculty time, what do you do? At Lipscomb University, they redesigned a traditional assignment into something impossible without AI: an individualized conversation between students and their 80-year-old future selves. The results challenged assumptions about student resistance to AI, revealed unexpected insights about conversational interfaces, and proved that sometimes the best way to teach with AI is to have students build it themselves.

Abby Bell and a team of professors faced a classic higher education paradox. As part of Lipscomb University’s freshman seminar program, over 750 incoming students each semester participated in a course that included a learning activity designed to engage them in deep reflection about who they wanted to become. The traditional assignment asked students to write a letter from their future selves, a meaningful exercise in theory. In practice, students could easily outsource the entire task to ChatGPT, submit something generic, and never engage with the reflection that the assignment was designed to prompt.

More fundamentally, the assignment format itself had become obsolete. A one-way letter captured in a single moment could not adapt to individual students’ unique strengths, circumstances, or questions. What these students needed was something closer to a conversation, a back-and-forth exchange that could help them think more deeply about their goals and values. But having personalized conversations with 750 students was simply impossible.

Reimagining the Impossible Task

Rather than abandon the assignment’s core purpose, Abby reimagined what it could become with AI. The new design had two AI components: first, an AI agent built with JotForm AI would teach students how to complete the assignment through an interactive presentation. Second, students would use BoodleBox to build their own chatbot representing their 80-year-old self, then have a conversation with that bot about their future.

The shift from letter writing to bot building changed everything about the assignment’s pedagogical potential. Students would need to think carefully about who they wanted to become in order to train their bot effectively. They would need to incorporate their StrengthsFinder results and reflect on an interview they conducted with someone they admired. They would need to develop language skills and higher-order thinking to prompt the bot appropriately. And they would engage in an actual conversation rather than producing a static document, allowing for the kind of dynamic exchange that deepens reflection.

This assignment solved what I call a “nearly impossible task,” the kind of pedagogical goal that becomes achievable only through Human+AI collaboration. Without AI agents, individualized guidance for 750 students requires either impossible faculty time or settling for generic, one-size-fits-all approaches. With AI, each student could have a completely personalized experience while faculty focused on the meaningful human work of reviewing and responding to student reflections.

Building an AI Teacher’s Assistant

The JotForm AI agent became the assignment’s instruction manual, but one that could adapt to student questions and needs. Abby built the presentation slides, incorporating checks for knowledge throughout, then trained the agent to walk students through the process of building their own bot.

The training process revealed important lessons about AI agent design. When Abby had someone test the bot as a complete novice, she got stuck on the very first step: figuring out how to access BoodleBox. This led Abby to refine the agent’s instructions and add a form that allowed students who were truly stuck to schedule one-on-one help. Each time the agent responded in a way that did not match what Abby intended, she could provide feedback and retrain it, iteratively improving the experience.

The platform’s robustness surprised even Abby. JotForm had originally designed this agent capability for hotels to showcase their amenities. Abby immediately recognized it as the future of online education, a way to create dimensional, interactive learning experiences that went far beyond static videos or documents.

Confronting Student Resistance

The fall 2025 cohort of 750 freshmen brought their high school experiences with them, and for many, those experiences included strong anti-AI messages. Creative students in particular pushed back initially, viewing AI as a threat to authentic expression.

Abby and her colleagues responded by adding an ethics conversation before the assignment itself. They framed AI tools like large language models as similar to other tools required in professional settings. Sometimes your employer wants you to use a black pen, sometimes blue, sometimes a pencil. The skill is knowing which tool to use and how to use it responsibly, not avoiding tools altogether. They shared statistics about employer expectations and positioned the assignment as preparing students for a future where these capabilities would be essential.

The framing worked. Most students moved from resistance to curiosity once they understood the assignment as skill-building rather than replacement of human creativity. One creative student who initially refused to participate became deeply engaged once she started building, ultimately training her bot to use Marvel quotes to offer advice. She recognized bot creation as its own form of artistry, requiring creativity and careful thought about language and personality.

The Unexpected Interaction Gap

The assignment achieved its primary goal. Students successfully built bots, had conversations with their future selves, and reflected meaningfully on who they wanted to become. The feedback was overwhelmingly positive, with students recognizing the tool’s future usefulness even when they felt uncertain about using it themselves.

But the data revealed something unexpected. The JotForm AI agent logged 752 uses outside of testing, but only about 5 percent of students actually engaged conversationally with the agent. They consumed the information it presented, but rarely responded to its questions or asked their own questions to get more information.

This lower-than-hoped interaction rate points to a larger challenge in AI adoption. Students’ previous experiences with technology have been primarily command-based. Siri and Alexa respond to directives, not conversations. Students lack a mental model for what it means to have an actual back-and-forth exchange with an AI agent, even when that agent is explicitly designed to help them.

The gap is not about technical literacy. These students can navigate complex platforms and learn new tools quickly. The gap is about imagination. They struggle to envision a world where conversational AI is woven into daily life, where talking to an agent is as natural as talking to a colleague.

Design Fiction as Pedagogical Scaffolding

This imagination gap suggests an important addition for future iterations of the assignment. Before asking students to build and interact with conversational AI, they need help envisioning what that future looks like. Design fiction, a strategic foresight methodology, offers one approach.

Rather than explaining conversational AI as a theoretical possibility, design fiction asks students to inhabit a world where it already exists. What does your day look like when you regularly consult with AI agents? How does it feel to have a conversation with a bot that knows your goals and strengths? What changes in your work and learning when these tools are commonplace?

By setting this context first, students can more easily understand what they are building and why. They can imagine themselves using these tools not as a strange experimental assignment but as a natural part of their future lives. The assignment becomes less about novelty and more about preparation for a world that is rapidly approaching.

Lessons for Scalable Innovation

Abby’s iterative approach to assignment design offers a model for other educators considering AI integration. The assignment evolved through multiple conversations, user testing, student feedback, and data analysis. For the next cohort, she plans to break the original components into smaller, clearer pieces and add better framing for how students should interact with the teaching agent.

The assignment also demonstrates the power of low-risk experimentation. Students who mess up their bot will not fail out of college. The stakes are intentionally low, creating space for creative exploration and learning from mistakes. This approach helps students who arrive with anti-AI attitudes from high school to develop more nuanced understanding through hands-on experience.

Perhaps most importantly, the assignment acknowledges that agentic AI represents where society is headed, whether we are comfortable with it or not. The moment Lipscomb adopted BoodleBox campus-wide, as one professor noted, was like the moment the whole campus got email. There is no going back. The question is not whether students will encounter these tools but whether they will have guidance and practice in using them responsibly and effectively.

The Future of Self-Discovery

Looking at the range of bots students created reveals the assignment’s deeper success. Some were surface-level, completing requirements without much depth. Others showed remarkable creativity and genuine engagement with the reflection process. Students reported that building the bot made them think seriously about who they wanted to be when they grow up and how they wanted to exist in the world.

That metacognitive work, the thinking about thinking that lies at the heart of liberal education, happened because the assignment format demanded it. You cannot train a bot to represent your future self without clarifying your values, strengths, and goals. You cannot have a meaningful conversation with that bot without engaging seriously with those questions.

The technology made this level of personalized reflection possible at scale. But the technology alone did not create the learning. Careful assignment design, thoughtful scaffolding, explicit ethics conversations, and iterative refinement transformed a potentially gimmicky use of AI into genuine educational value.

What Comes Next

As Abby prepares for the spring cohort and plans for fall 2026, she is considering several refinements. An A/B test comparing different avatar styles could provide valuable data for this specific context. Research on avatar design for education is nascent and remains inconclusive. Some studies suggest realistic avatars may trigger discomfort (the uncanny valley effect), while others find no such effect. Early research, including a small pilot study at Emory University, found that students performed well when learning from human-created content delivered by AI avatars, though researchers note this needs expansion and further testing.

The assignment components may be further unbundled, with clearer separation between the interview and transcript creation phase, the reflection and bot training phase, and the conversation and letter writing phase. This additional scaffolding could help students who felt overwhelmed by the original all-in-one approach.

And the design fiction addition could help bridge the imagination gap, giving students a clearer vision of the conversational AI future they are preparing to inhabit.

Why This Matters Beyond Lipscomb

This experiment matters because it tackles one of higher education’s most persistent challenges: how to provide individualized attention and guidance at scale. The traditional answer has been to accept lower quality, one-size-fits-all approaches as the price of serving large numbers of students. AI partnerships offer a different answer, one where technology handles the scalable parts while humans focus on the irreplaceable work of meaningful connection and support.

The experiment also matters because it demonstrates how to introduce students to AI not as a threatening replacement but as a tool they can understand, control, and adapt to their own needs. By having students build the bots rather than simply use pre-made ones, the assignment demystifies the technology and empowers students as creators rather than passive consumers.

Finally, the experiment matters because it shows that resistance to AI among students is neither universal nor permanent. With appropriate framing, ethics conversations, and low-stakes practice opportunities, even skeptical students can develop more nuanced and productive relationships with these tools.

The future Abby and her colleagues are building at Lipscomb is not one where AI replaces human guidance and reflection. It is one where AI makes human guidance and reflection possible for all students, not just the privileged few. That future is worth building toward, one bot at a time.

Brilliant! How do you prevent prompt engineering from undermining reflection?